REVOLUTIONARY OUTRAGES;

Or, WILDE, VERA AND COOKERY

“This is no time for wearing the shallow mask of manners. When I see a spade I call it a spade.” “I am glad to say that I have never seen a spade. It is obvious that our social spheres have been widely different.”

This is, of course, one of many fabled exchanges in Wilde’s last play, The Importance of Being Earnest which was staged (1895) fifteen years after his first, Vera to which one might turn in eager hopes of seeing a spade in action. Why is that? Set, during its opening scenes, in the Russian, even Siberian countryside, it includes a peasant, Michael, who has designs on taking something even sharper in his hands: “one dagger will do more than a hundred epigrams.”

Here, in the world of the Nihilists, is the melodrama to which Wilde would be more given than his drawing rooms might at first suggest (and at its height in his only novel).

That said, there are metropolitan scenes and such dialogue as “You haven’t quarrelled with your cook, I hope? What a tragedy that would be for you; you would lose all your friends.” That is cynically good in its own right, but, as Wilde would so often show, the line this provokes makes it all memorable (as with the spade). Prince Paul replies, “I fear I wouldn’t be so fortunate as that. You forget I would still have my purse.” To continue the food theme, “Francatelli’s really excelled himself in his salad. Ah! you may laugh, my worthy minister of Finance; but to cook a good salad is a much more difficult thing than to cook the books. To make a good salad is to be a brilliant diplomatist - the problem is the same in both cases. To know exactly how much oil one must put with one’s vinegar.” “A cook and a diplomatist! an excellent parallel. If I had a son who was a fool I’d make him one or the other.”

Such moments make one wonder whether Wilde relished that novelist-gourmet Thomas Love Peacock who would surely concur with the Prince’s further observation, “believe me, you are wrong to run down cookery. Culture largely depends on cookery For myself, the only immortality I desire is to invent a new sauce. I have never had time enough to think seriously about it, but I feel it is in me, I feel it is in me.”

Events move away from the dinner table, another liquid comes on this scene. Wilde turns to the end of a Czar who has been warned, “the people suffer long, but vengeance comes at last, vengeance with red hands and silent feet”; that is very good, those “silent feet” are an improvement on Wilde’s first draft of “bloody purpose”. How do we know this?

The recent Oxford edition (2021) of the play, along with Lady Windermere’s Fan, has been made with steady diligence by Josephine Guy which is a contrast with the on-the-hoof way in which Wilde had set about it a hundred and forty years earlier (such as adding the countryside prologue). He made that “silent” change, and the text here presents the 1882 text (as revised the next year when it was briefly staged in New York, along with some of the alterations and additions that emerged after Wilde’s death).

Had Wilde written nothing more, perhaps, as with so many books, it would have gone no further than its first private or, at least, modest editions. That is no reason for not according it now full attention as part of a body of work which, as with Lawrence’s, was to find Wilde accomplished in many forms (it took decades for the author of Sons and Lovers to be appreciated as a playwright).

And so close attention is even paid here to the title. Josephine Guy settles for Vera; Or, The Nihilist. Rather than, as some did, turning the sub-title into the plural, this keeps the focus on the barmaid daughter of inn-keeper Peter instead of the circle of the variously disgruntled in which she will find herself in what the first editions located as either 1795 or 1800 instead of the indeterminate, near-contemporary period of the final text (which could also be said to comprise an amalgam of St. Petersburg and Moscow).

The prologue finds Vera witnessing a chain of men literally bound for salt-mine incarceration. Among them is her brother, who urges her to leave Siberia and join those attempting to liberate the country from the Czar. She does so, and so well that she becomes renowned as a killer (“she is as hard to capture as a she-wolf is, and twice as dangerous”). All of which, with some refinement, could be the stuff of a contemporary Hollywood film, complete with one of the Nihilists, Alexis being both the object of her desire and - as it emerges - heir to the throne, which becomes his after that murder of the Czar.

A turn to events which brings him the throne - and makes him the Nihilists’ fresh target.

His taking out is assigned to Vera who, inside the palace, cannot bring herself to perform the task, such are her continuing feelings for the man (“I am a woman: God help me I am a woman: I thought I had been made of iron and steel, I am only a common woman after all.”). She does, though, manage to hurl the bloodied dagger from the window as a sign to the others that she has done the deed - in fact she had turned it on herself, and expires with the play’s wonderfully wild last line, almost Garbo, “I have saved Russia!”

Wilde had that line in mind from the start. It appears in the manuscript version which Josephine Guy supplies in all its unformed fascination. There it appears a page before curtain down, and it is often as if the manuscript is a series of jottings, lines in search of their place, a play whose characters will shape up alongside the words themselves (one can study the full evolution of the salad/diplomacy exchange).

The playwright was learning - and soon realised that his first scene, in which, by turn, Nihilist members introduce themselves and their motives at a gathering, was very dull and would make for stage-bound tedium. His later creation of the Siberian prologue was inspired. Equally, a long summary of pan-Europe discontent (“the heart of Poland is sick to death”, and so on) is ditched. We are made aware by other means that this gathering is part of something greater. One might even recall Algernon’s news that Bunbury was “quite exploded”, which brings Lady Bracknell’s reply, “Was he the victim of a revolutionary outrage? I was not aware that Mr. Bunbury was interested in social legislation. If so, he is well punished for his morbidity.”

Morbidity could be called a motif of Wilde’s first play. Despite that influx of epigrams in the Palace scenes, the tone is sombre - and more effective than some might grant, what with its Shakespearean and Biblical cadences. Another absorbing part of this volume is Josephine Guy’s long introduction. A substantial section of this provides background to the contemporary fascination with Nihilism, which continued after the attempts to stage a play which some have seen as an allegory of the situation in Wilde’s native Ireland (Sos Ellis’s 1996 Revising Wilde was along those studies to see the plays in a more political context).

Many were the contemporary articles and books at the time about Nihilism (a term which appears to have first appeared in Turgenev’s Virgin Soil), and the introduction lays some emphasis upon John Baker Hopkins’s 1880 shocker in which a villain has the accomplice “Clegg the Destroyer. Dipped-dagger Clegg. Kill-shot Clegg. Air-poison Clegg”. Evidently you messed with Clegg at your own peril.

There is so much to discover in a play too often flicked aside in perusal of a one-volume collection of Wilde’s works. To see it staged would be more than a curious evening out. We have become accustomed in recent years to productions of Earnest with Lady Bracknell played by a man. A decade ago, in New York, a drag artist took on the rôle of Vera with the intention of showing how, long after Nihilist discontent, there was now a fearful situation for gay rights in Putin’s Russia.

As it happens, New York was again to figure in the history of the play. Soon after Josephine Guy’s edition appeared, there was an article in the journal Notes & Queries. One almost shies from drawing attention to it, for it is every editor’s nightmare: she had overlooked something which was sitting all the while in the Berg Collection of manuscripts at the city’s lion-guarded Public Library on Fifth Avenue. In the article, Rob Marland points out that Wilde was more than tinkering again with the play for its 1883 staging there, so much so that he wrote a speech which, at the end, finds Alexis declaring at some length his love for Vera and refers to her lips as “portals” - a word cited in a review of the production. Marland also cites reviews which suggest that moreover, at least in some performances, both Vera and Alexis died, she still managing to hurl the dagger from the window after he had turned it upon himself with the declaration, “all the turbid passions of my life seem reduced to one ecstacy.”

So much for the dagger. One might yet return to the spade as another sign of Wilde’s interest in social legislation. He certainly saw, perhaps used one. At Oxford he was one of those undergraduates, including Arnold Toynbee, who were prevailed upon by Ruskin to help repair a road off North Hinksey Lane. How much Wilde dug is uncertain but, in contending with work on those potholes, he was certainly entrusted with the Professor’s wheelbarrow.

This is almost as unlikely a vision as his appearances in The Simpsons (one of them as a ghost). One can well imagine that Wilde would have been as flattered by that as by this place in this venerable, dark-blue-and-gilt series of Oxford English Texts. He might, in passing, also wonder whether Mr. Burns’s gay, bow-tied sidekick Smithers took his name from the dodgy publisher who was none the less brave enough to publish Wilde after release from Reading Gaol.

His posthumous edition of Vera, issued in 1902 (not to mention those 1880s versions seen by by Wilde), now commands a sum which dwarfs the price Oxford asks for Josephine Guy’s edition which, into the bargain, includes two versions of Lady Windermere’s Fan - but they are matter for another day.

A CONVERSATION WITH WILLIAM BOYD

Refulgent mid-February sunshine makes the bar at the Chelsea Arts Club glow. Nine months on, that now seems another era, when William Boyd - in a smart jacket offset by an open shirt collar - was sitting, a glass of red wine to hand, soon after completing his sixteenth novel, Trio.

That winter's day, we were about to talk of this book, and more, when the barman leapt from his position and, in a bound or two, stood beside a man in a deep-winged armchair the other side of a large pool table. The barman's task, effectively, politely done, was to remind the member, engaged in ardent talk, that cellphones cannot be used on the premises. The Club has indeed scarcely changed. One can well imagine Laurie Lee arriving, on his way back from the now-vanished Queen's Elm pub up the road - anything rather than get on with the sequels to Cider with Rosie.

What draws you, as a novelist, to places such as this? Naturally, I am also thinking of the rather more louche premises frequented by Elfrida in Trio.

Well, Chris, like most things in life it was down to luck. My wife Susan and I had just moved to London from Oxford - this was 1983 - when the Chelsea Arts Club appointed as managing director someone we knew - a man called Dudley Winterbottom, who used to run a restaurant in Oxford called The Cherwell Boathouse that we regularly patronised. The club was in a bad way and desperately needed new members and Dudley said - do you want to join? We said yes, please. Easy as that. So we’ve been members for 37 years, now. We didn’t use it so much when we lived in Fulham but as we’ve lived in Chelsea for the last 33 years we’ve become regulars. It’s a unique institution - incredibly relaxed. And because most members are artists or associated with the arts it’s full of like-minded people with the same values. Unstuffy, a bit eccentric, good sense of humour, very cultured, animated, fun.

I like places - bars, restaurants, clubs - with “character” and as we’ve travelled round the world we collect places we like to hang out in. Bemelman’s Bar in New York, say, or the Café de Flore in Paris - and places we revisit in Madrid, Barcelona, Berlin and so forth. It‘s the same with pubs - certain pubs possess a vibe you respond to - others don’t. Elfrida in Trio warms to the Repulse and its denizens, “The Repulsives”. It suits her.

Yes, Bemelman's was a great spot. I found myself next to Tony Bennett at an opening night of Barbara Carroll's there. It was, as Cole Porter's song has it, just one of those things. He talked about Bill Evans, free and easy. Anyway, here and now, an interview usually takes place some while after a novel is completed. How does it feel right now, when you have begun to send it to editors, translators and so? Auden was fond of quoting Paul Valéry's remark that a poem is never finished, only abandoned. How does one come to let a novel go?

Usually because you’re contractually obliged to deliver. Or you know what a publisher’s schedule is and you want your novel to be published in a certain season. So you count back nine months or a year and you say to yourself: that’s when it’s got to be done. I’m rather thinking, now I’ve delivered Trio, that I’d like my next novel to be published in September/October 2022. So I’ll have to deliver it in, say, January 2022. Which is actually not very far off, I’m rather shocked to realise. I’d better get on with it.

Sitting here, in this timeless Club, it's startling to think that we are now as far from your first novel, A Good Man in Africa, as that was from the beginning of the War. It makes me think that in your novels you have taken the twentieth century as your subject. They have an impressive range of time and place. How conscious were you of setting out to do this? And how much is owed to chance - the subconscious, perhaps - in lighting on a subject?

Not conscious at all. There was never any grand plan - just the next novel to be written. Of course, the more you write, hindsight allows you to see the prevalence of certain themes, certain tropes. I now realise that I’ve rather concentrated on a sub-genre of the novel, the “whole-life” novel, as I’ve called it: a cradle-to-grave novel. Quite hard to write, actually. The first one was The New Confessions in 1987. My next novel will also be a whole-life novel. By definition they tend to be long - five-hundred pages or so. I have written four of these whole-life novels - five if you count Nat Tate.

As for the twentieth century, I tend to think of it as my century, even though we’re two decades into the twenty-first century. I was born in the middle of the previous one. I knew people very well who were born in the nineteenth century (my grandmothers, for example). For me the whole of the twentieth century has a feel of being contemporary, not the historical past.

Also, looking back, all my novels are very different from one another - even though they may share certain themes. You might be able to classify some as comedies, some as “African” novels, or the whole-lifers - but the only thing that stimulates me is the desire to write a particular novel, to tell a particular story involving certain characters I’ve invented. My next novel will be entirely different from Trio. Do you fancy another glass of wine?

A good idea! And now, with Trio, you have landed in Brighton (with, of course, salutary forays to Hove, including its then-unfashionable Portland Road). This is, naturally, territory which brings with it the great shadow of Graham Greene. Hove appeared very briefly in Stars and Bars, and more so in Sweet Caress (where you provided it with the Westbourne Lido, complete with photograph) Why Brighton now?

I think it’s because of this strange obsession I have with East Sussex. East Sussex has featured in a lot of my novels. I’ve even invented a village, Claverleigh, that is near Lewes. I feel I could go and visit it - maybe even buy a house in it, it’s so visually present to me. I know lots of people who live in and around East Sussex and Kent - and a few in West Sussex, even. I find the South Downs incredibly beautiful. And so many writers were drawn to this part of the world - Conrad, James, Benson, Wells, Ford, Woolf, all the Bloomsburyites - and many others. Close to London, yet far enough away from London.

As for Brighton, two close friends live in Hove (you and Derek Deane, the choreographer). My goddaughter, Flora, went to Sussex University. My young cousin, Lizzie Boyd - a brilliant jazz and soul singer - lives and works in Brighton. So I’ve visited the place regularly. I’ve written a lot about London and decided to move out of town for Trio. Brighton has this slightly rackety reputation and so it suited the mood and atmosphere of the novel, especially the 1968 version of Brighton.

Greene said that he had invented his Brighton, and yet had to live ever after with people thinking it rife with gangsters. The Council was all the more vexed at the time, in 1938, because confectioners' signs - Buy Brighton Rock - were subliminal advertising. Your Brighton is 1968, a year of apparent revolution (which included that Beatles' song) and of municipal architectural horrors - such as the advent of the concrete Churchill Square in Brighton. Which is ironic, as Churchill once said we create our buildings and then they create us. It seems to me that buildings of all kinds are to the fore in Trio. Was this a conscious intention?

I think it’s part and parcel of the way I write. I’m a realistic novelist, therefore the buildings and landscapes of my novels have to be rendered realistically. I spend a great deal of effort thinking about the houses my characters live in and I describe them accurately but not pedantically, I hope. I’m interested in architecture - I’m always poring over The Buildings of England. I’ve lots of manuals of building, and building trades, encyclopaedias of architecture and the like. All in the interests of getting it “right” and adding proper, detailed texture. In my novel The Blue Afternoon the narrator, a young woman, is an architect who is building Streamline Moderne houses in Silverlake, Los Angeles, in the 1930s. It’s fascinating researching this stuff. But you mustn’t overload your novel with your research - less is more.

In writing a novel, how much detail do you find is needed to keep things moving forward, as your novels always do? Dickens, I know, inspired you, but I think you hold back from his approach?

You are always looking for the single detail that will do a lot of work for you. I think of the novelist as a kind of magpie, not a scholar, looking for the gleaming nugget of detail that will illuminate the period, place or profession that you’re writing about. Dickens is brilliant at mise en scène. So is J.G.Farrell, by the way - though he went a bit out of control with The Singapore Grip which gets very ponderous as we’re told all about how rubber is manufactured over nine pages. The Siege of Krishnapur and Troubles, by contrast, are exemplary in how to conjure up the past with seeming effortlessness. You do masses of research and then maybe use ten percent. You must strongly resist the temptation to shovel it all in - it’s very easy for a novel to sag under the weight of its detail. In the end I think it’s a matter of instinct. I think I’ve taught myself exactly how much is just right, just enough.

This leads us to one of the three main strands of Trio. It turns around the making of a film with one of those preposterously long Sixties-style titles. As well as the vexations endured by its producer and star, there is a blocked novelist, Elfrida who has hit upon the idea of a novel about Virginia Woolf's last day, which was at the beginning of the war - far closer to 1968 than we are. She struggles with the opening paragraph. You provide many versions of this paragraph. Was that fun to do? Is it borne of experience? Are you one to read author's early drafts, such as those by Mrs. Woolf and Scott Fitzgerald?

It was actually great fun to do but in fact it’s a nod - or an act of homage - to Albert Camus’ novel La Peste in which there’s a character, Joseph Grand, who is trying to write a novel. Grand is obsessed with the opening of his novel but is such a perfectionist that he never gets beyond the first sentence. The novel is studded with his various attempts to get it perfectly right. It’s actually very funny. I’m fascinated by Camus and there is a Camus quote as an epigraph for Trio - which is meant to alert you to the homage. But, until the recent onset of this pandemic, I think La Peste was little read - then suddenly everyone's quoting it. Elfrida actually refers to La Peste at one stage but she can’t quite remember the title.

I’m not one for early drafts - except the long version of The Waste Land that Ezra Pound brutally redacted to make the poem we know today. It is fascinating to see what Eliot had intended, how prolix it was, and how Pound - il miglior fabbro indeed - through his wholesale edit saved, if not created, the poem, in a very real sense. A bit like Raymond Carver and his editor, Gordon Lish. Lish’s drastic cutting and re-ordering of Carver’s stories created the Carver voice and made Carver’s reputation - as Pound did, in a way, to The Waste Land. Though Eliot is a major poet in his own right, of course. I don’t think we would rate Carver today, however, without Lish’s ruthless surgery. Lish and Carver are like Maxwell Perkins and Thomas Wolfe. The editor was, let’s say, just as creative as the author. Such a situation is very rare, however.

I have always been fascinated by authors' use of words, how one keeps the compost heap of vocabulary turning over. All have their tropes without going in for the wordplay (Lorne Gyland) of Martin Amis whose wordplay often seems to me, shall we say, hoarseplay. All of this leads up to noticing that again you use the great word “refulgent”. When it appeared several times in your essay collection Bamboo, Adam Mars-Jones spluttered in a review. I should think he will go beserk to see it again here - and indeed that passage, about the Channel, is promoted to the back cover.

I think all writers have a private vocabulary of words they use all the time. I like the word “refulgent” and there are many others I call into service. “Dun” is another one. Certain colours are always re-used by me, also. I like a word like “cerise” or “ultramarine”. You don’t have to add the word “colour” to them. Of course, in an essay collection - articles written over decades - this tic is all the more noticeable. I made a point in the introduction to Bamboo of saying that I deliberately hadn’t removed repetitions - I’m always re-using certain quotations and references also, the same old names and citations recur. I decided not to clean up the articles and tinker with them after the event to make me look better. It’s always a good idea for a critic to read introductions. They are there for a purpose, like epigraphs.

In 1968, interest in Virginia Woolf was beginning to grow again. Penguin editions were regularly reprinted in the Sixties, Leonard had written most of his detailed memoirs - and, at Leonard's behest, Quentin Bell, who had written so well on Ruskin, was writing a biography of her, his aunt, which appeared in 1972. Two years later she was depicted on stage by the great Yvonne Mitchell in a bad play by Peter Luke (with a good turn by Daniel Massey as Lytton Strachey). There has since been a spate of novels about her, the first was in French - and lately there has even been Mitz, a Flush-style novel about the marmoset whom she and Leonard adopted in the mid-Thirties and who accompanied them on a dangerous journey around Germany. There is diverse interior monologue in Trio. How much does the writing of novels in general now owe to Modernism, how much has it been a blight? Which reminds me of that question from the back of the room in The Third Man, “where would you place James Joyce?”

I think that as far as the realistic novel is concerned, Modernism hasn’t made or doesn’t make much difference. In the same way as figurative painting hasn’t really been affected by abstract painting. There’s nothing in the paintings of Lucien Freud, for example, that would astonish John Singer Sargent (apart from the explicitness). Technically they belong in the same world even though they lived and worked a century apart. The realistic novel has borrowed from the modernist novel - stream of consciousness, for example - as it suited the purpose of the author. You can fracture narrative, change pronouns, be expressionistic, employ elision, or allusion, whatever you like, and still regard yourself as a realistic novelist in the way that Freud is essentially a figurative painter, like Ingres, like Giotto. The broad river of figuration, of realism, is untroubled by the experimentation flaring up and dying away around these great traditions. I think I’m a good example. Some of my short stories are quite experimental, however - I’ve used illustrations, very unreliable narrators, and so on. Sweet Caress has seventy-three “found” photographs in it. Perhaps my art hoax, Nat Tate, employs those playful, Ouliponian elements of the modernist novel but it still apes the form of the art monograph/memoir.

Your remarking that your short stories often take an experimental turn makes me reflect that you have a penchant for such poets as Wallace Stevens whom one might call elliptical. And you have written on Auden's The Orators. And indeed Pessoa, I know, is a favourite of yours, a writer who assumed many guises - or, as he called them, heteronyms. I also wonder what draws a writer to focus on novels or poetry? Few write both, though there are Wilde and Lawrence, Hardy.

Yes, I am a great reader and buyer of contemporary poetry. I have several hundred slim volumes. I have a theory that serious novelists are great readers of poetry - but rarely poets. No-one has ever done any investigation but there is something about the precision of language that poetry employs (if it’s good) that is very alluring to novelists. We do have to write such lines as, “He got out of the car and walked up to the front door” - novels demand that type of expository prose - but you can’t write a proper novel only using the charged language of poetry (“Language on points” as Craig Raine expressed it) as it would seem unreadable and precious. Ezra Pound said, “Poetry should be at least as well written as prose” and I think that all novelists who care about the texture and nuance of their prose are aware of the poetic example, and employ it from time to time for a paragraph or so.

The elephant in the room here is Finnegans Wake, to pick up your reference to Joyce. The novel written as poetry - and pretty much unreadable, let’s be honest. Say no more.

The first writers that I met and came to know who were my peers were poets. We are talking Oxford in the 1970s. Craig Raine, James Fenton, Andrew Motion, Alan Hollinghurst, Jamie McKendrick, Tom Paulin, to name the most celebrated. My pantheon of poets alters a bit over time but is pretty consistent. Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney, Craig Raine, Christopher Reid, W.H.Auden, Elizabeth Bishop, Wallace Stevens, Paul Muldoon, Alice Oswald, Marianne Moore, T.S.Eliot, Jamie McKendrick, Don Paterson, Michael Hofmann, Ted Hughes, Louis MacNeice, Derek Mahon and a few others. As I say I am a great consumer and buyer of contemporary poetry.

Is it a paradox, then, that so few great novelists are also great poets? Thomas Hardy (whom Larkin revered) is perhaps the most striking example. Kipling - yes. George Meredith? There are many poets who have written a novel or two (Raine, Motion) but very few novelists who have published their own slim volumes. Blake Morrison? He sort of covers both art-forms. Kingsley Amis? Anthony Burgess wrote some very good poems. But would you describe them as “poets”? I’m not sure. You are either one or the other and a very, very few are allowed both labels. There’s a young, very clever poet called Luke Kennard who has published one novel. And another very good poet, Adam O’Riordan - who seems to be moving into the world of prose fiction with a collection of short stories and a novel due to appear. My own feeling is that it’s very hard to practise - to practise well, with sophisticated proficiency - more than one art form. Think of the novelist/painters, the novelists/composers - they are as rare as the novelist/poets.

Lord Berners comes to mind, but he was a unique novelist, painter, composer praised by Stravinsky, and there's an interesting recent rise in verse novels, such as Robin Robertson's. Meanwhile, of course, in the time since your first novel, technology has changed as much as it had between 1941 and 1981 - the clunk and whirr, the crumpling jam of fax machines has come and gone, its shiny paper soon invisible ink, and so has the wire-fence twanging of modems' connection. How does a novelist cope with this? Richard Hannay can no longer leap upon a train to Scotland and be out of range. Elfrida would be able to click on a search engine - as you showed in Ordinary Thunderstorms - to seek information about Virginia Woolf rather than arrange for lunch at the Tate.

I think that explains some of the attractions of setting a novel in the past, even the recent past. The risk of built-in obsolescence is radically diminished. Setting a novel today is almost inviting it to date. How could you start writing a contemporary novel today and ignore the spreading of this pandemic? It would be crazy. I’m writing a short story at the moment and I have deliberately set it in January 2020 so that the virus doesn’t need to be referred to. People aren’t wearing masks. Then, when you write your Covid-19 novel it’s going to seem very old hat in two or three years' time. You and I had a friend, the late Justin Cartwright, who wrote very up-to-the-minute novels. I remember in one novel there was a kind of repeated riff about a try scored by Will Carling in a crucial England-France Six-Nations rugby match. What match was that? Who is this Will Carling? He’s a forgotten man - his fame, his réclame, has almost totally disappeared. Future editions of the novel will need a footnote to explain the significance of the epiphany. Extremely contemporary details in a novel are almost inviting it to be superannuated very swiftly. Not a fate to be wished for.

Naturally, one of the fascinations of Trio is its day-to-day account of coping with the problems in making a film - not least the shifts needed in altering a plot to cope with an absent actor or an additional one. This makes me think of Truffaut's glorious La Nuit Ameriçiane, in which Greene had an undercover cameo - one of his practical jokes - to advise on just such an incident. How does working on a film, as you have often done, compare with sitting at a desk where all is at your command?

Well, I’ve written a lot about the difference between writing novels and films. Briefly, writing a novel allows you to occupy a world of total freedom - it is the most abundantly generous of art-forms. Writing a film, by sharp contrast, sees you in a world of parameters, compromises and sheer impossibilities. Film is photography. It may seem a banal statement but therein lies the medium’s draconian impositions. There is one over-riding point of view - the camera lens. Film is monstrously objective - you, the audience, the viewer, are always looking on. Consequently, subjectivity - something the novel handles almost unthinkingly, with tremendous facility - is very hard to achieve and in film the tools at your disposal are crude: good acting, voice-over, using the camera as a person’s point of view. But the best actor in the world cannot convey the subtleties, the nuances of nuances, that can be found in a paragraph of internal monologue or reflection in a novel. Of course, film has its wonderful strengths but it’s important to realise that film and the novel are radically different art-forms. You need a complete change of mental gears when you move from the novel to film and back again - as I do. They are both narrative art-forms, true, but somebody once came up with a good and telling analogy. Writing a novel is like swimming in the sea. Writing a film is like swimming in the bath. You may be “swimming” in each case but the two experiences are not really relatable. It may seem an over-the-top comparison but it’s very close to the reality.

But then when a film is made there are great satisfactions for the writer when you go to the set. All these hundreds of people trying to make your words suddenly real and three dimensional, your characters incarnated in particular actors. I enjoy the collaboration. I enjoy the company of actors - many of my friends are actors - and I enjoy the fun and glamour and excitement of the movie or TV business (there is a harsh down-side, also, much less fun). But there’s no doubt that I would describe myself as a novelist, first and foremost.

And, of course, film production is even more fickle than publishing (Kazuo Ishiguro has said much the same of the music industry and publishing). It's a shame that your mooted work with Mel Smith on The Galapogos Affair and with John Schlesinger on the Edinburgh-set The Loss-Adjusters did not work out.

Yes, it’s a terrible business, in the economic, entrepreneurial sense. Filmmakers and the “industry” are pitted against each other, their value-systems wholly contradictory. That’s where all the horror stories come from. In my case, if I didn’t get a film or TV series made every couple of years I’d pack it in - the fights, the struggles, the betrayals, the idiocies just aren’t worth it. Making the film is the great achievement, the great pleasure, that compensates for all the problems and all the deeply stupid, venal people you are forced to deal with. I have written around sixty-odd screenplays over the years and have had twenty films and TV series actually made. That is a great strike rate in the business. But there are at least half a dozen unmade films that still haunt and bug me. But never say never. I hope that next year we will shoot a little movie based on my short story “Cork”. Fingers crossed. It’s cast, we have a director, it seems financed. This project has been underway for twenty years - maybe it will finally see the light of day.

Sixty screenplays! To outsiders it can look a doddle to write EXTERIOR. DAY. BERLIN 1961 - and then a whole bunch of people work on setting up such a scene. I mention this as you have also been creating a six-hour television series Spy City, which is to be shown later this year. How does the apparent shorthand of writing a screenplay compare with the long, descriptive process of a novel? Is it more akin to the short story? You have written five collections of these, which, as you said earlier, range widely in narrative approach.From the beginning, with On the Yankee Station, these espoused the experimental, such as “Long Story Short”.

I think screenwriting is a craft rather than an art. In a way, the less “writerly” the screenplay, the better. As I said, you have to change mental gears. One page equals one minute of film. Verbosity is counter-productive. So you transform your writing style into something punchy and instantly able to be visualised. Dialogue is another matter - in that case whatever naturalistic skills you have can be an asset.

And there is no comparison to the short story, actually. The same novel-film distance applies to the short story-film relationship. Except it is better to adapt a short story for a film rather than a novel because with a short story you have to write extra material. Adapting a novel involves throwing out fifty percent - at least. Again, this shows up the stark contrasts between the two art forms. Long-form television is a different beast - some of the meanderings of the novel, its diversions and sub-themes, can be easily incorporated - the story can “breathe”, as they say, you are allowed longueurs, it’s not just cut-to, cut-to, cut-to. But you still have the fundamental problem. It’s photography; it’s monstrously objective. Getting inside people’s minds is very, very difficult and, speaking as a novelist, your attempts in a film to replicate the complexities of someone’s interior life are ultimately unsatisfying.

Thinking again of Truffaut, he was dismissive of British film in general. Trio highlights that Sixties vogue for the, shall we say, “whacky” side of films with absurdly long titles. How does that fit with the earlier phase of trenchant realism, such as Saturday Night and Sunday Morning - and indeed did the two strands merge with If... - a very short title? There is surely a lot more to be said for British film than Truffaut allowed, such as Val Guest's 1962 Brighton-set Jigsaw, which was adapted from a novel set in, of all places, New Jersey?

I don’t think that’s fair, at all. It’s like the German composer who described Britain as a “Land without Music”. Open your ears! And the history of British film is very rich, in its own way. The sneers display ignorance. These generalisations are very easy to shoot down. French filmmakers are lucky because their industry has always been heavily subsidised. Our industry is a satellite of Hollywood, with a few exceptions. In a way there has been a reverse colonisation of the Hollywood film industry. It has been and is full of Brits - from Hitchcock and David Lean to Ridley Scott and Christopher Nolan. Very, very few French filmmakers have had any kind of success in Hollywood. But they don’t need to go there - because their subsidised industry allows them to make films for a French audience. We are carpetbaggers, in comparison, and remarkably successful ones.

To return to Brighton itself, I was reading on the train Richard Wyndham's contemporary account of “a last look round” Sussex ,Kent and Surrey in 1939 before War service ( part of the Petworth family, he survived, only to die in the Middle East in 1948). I have it here.He says that “the coast from Rottingdean to Newhaven is probably the nastiest mess in the British Isles” - but that is matter for another day, there was uproar when I described Newhaven. He also says, of Brighton, “the town's patrons also remain in clear-cut compartments - so isolated that they are unconscious of each other's existence. The phrase 'I'm off running down to Brighton for the week-end' is thrown out as casually by race gangsters, collectors of old musical boxes, hypochondriacs, curb crawlers in sports cars, patient pier-end fishermen or night-club queens - and always with the assumption that everyone visits Brighton for no other reason than their own.” Was this sort of thing in your mind for Trio? It is quite possibly the first novel in which scaffolders - with their boards and couplers - are to the fore as much as film-makers?

I don’t claim to “know” Brighton at all. But I did a lot of research - as I always do. I’ve written an entire novel set in the Philippines and have never set foot in the place. I wrote about cities that attracted me - Berlin, Lisbon, Los Angeles - long before I visited them. I sent my imagination as my avatar.

I think I chose Brighton because of its reputation as a kind of racy, exciting place where inhibitions could be set to one side. One of the characters in Trio describes Brighton as the “Las Vegas of England”. That may be a bit much - but you see what I mean. You feel can let your hair down in Brighton just as Americans from the Mid-West see a trip to Vegas as a kind of licensed bacchanalia.

As for scaffs - I’m very intrigued by the profession. There is a scaffolding firm in my novel Armadillo, for example. I did a lot more research about the business of scaffolding for Trio - and I have a new respect for the noisy so-and-so’s.

Yes, and it's even noisier now that they use electric devices. This makes me think that for a writer, film-making is a case of engaging with those of a practical disposition. Would you say that you have this? I know that you never learnt to drive. Nor did Graham Greene - and I was surprised at his daughter saying that she was startled in Antibes when he was about to summon an electrician to change a light bulb. He marvelled that she got on a chair to do so there and then.

Even though I don’t drive I think I’m quite practical. I can change a lightbulb. A lot of writers don’t drive, funnily enough. Could it be because we’re partial to a drink? Or because our attention wouldn’t be fully focussed on the road and the traffic? I learned to drive in my teens, but my parents’ car was in Africa and I was at school in Scotland. And then at university I couldn’t afford a car, and then I got married to Susan, who was and is an excellent, super-capable driver - and that was the end of my ambition to take to the open road.

That reminds me that Virginia Woolf started to learn to drive in the Twenties but promptly ended up in a ditch, and so that was that. Music has quite a part in Trio (as it did in her life). There are references to Jimmy Webb's epic “MacArthur Park”, which reminds me that George Harrison's “Badge” - I think one of his best songs, that guitar riff - played a significant part in your first film Good and Bad at Games. And, of course, music is the driving force of your previous novel Love is Blind. How does music inspire your writing life? Greene, for whom music did not do so, was surprised when Our Man in Havana became an opera by Malcolm Williamson - and claimed to prefer it to his novel!

Music plays a large part in my life but not in my writing life, particularly. I don’t listen to music as I write - though I listen to music all the time when I’m not writing. I think my tastes are very eclectic and wide-ranging. Interestingly, I am currently in the early stages of writing a musical with Jorge Drexler, a wonderful Spanish/Uruguayan singer-songwriter (he won an Oscar for Best Song for The Motorcycle Diaries) - and the libretto for a one-act opera based on a Chekhov short story with the British classical composer Colin Matthews. I’m not a musician but I’m a music-lover.

Things keep coming back to Brighton. That is the nature of the place. It occurs to me that, soon after the film in Trio, Richard Attenborough arrived in the town to make a version of Oh!What a Lovely War. Of course, he worked widely in films - not least as Pinkie in Brighton Rock, and I keep finding that he turns up in less well-known British films, such as The Man Upstairs. You got to know him well in writing the screenplay for his life of Chaplin. How much was he on your mind in writing Trio?

I was tremendously fond of Dickie Attenborough, and both Susan and I came to know him and his wife Sheila well during the arduous journey of getting Chaplin to the screen. I learned a lot working with him. He was very inclusive. I remember spending time in downtown Los Angeles with him as we did a recce for locations for the film. We all lunched in a Taco Bell one day. “This is delicious!” Dickie cried as he hoovered up an enchilada. He was a man without pretensions or “side”. I saw the harsh reality of Hollywood film-making while we were in LA at that time. Universal, who was funding the movie, suddenly pulled out - they said the budget was too high and demanded cuts - and I saw Dickie actually take the call to receive this very bad news. I was standing three yards from him. He rolled with the punch and had to set the whole thing up again (with Carolco, a big independent) so the whole film was delayed a year. Robert Downey Jnr loyally stayed on board and eventually the film was made. It was expensive for its era - $40 million dollars, about $70 million at today’s prices - and not really a very commercial prospect, to be honest. Dickie Attenborough was a completely delightful man.

Attenborough, often against the odds, made a success of so much to which he turned his hand. It has occurred to me, thinking of Elfrida's attempt to write another novel, that success or lack of it - from the hapless Morgan Leafy onwards in A Good Man in Africa - has been a theme of your novels. People are up against it time and again in so many ways.Is this, perhaps the human condition, a spur to write novels?

Funny you should say that, Chris. A very early review of my first collection of short stories, On the Yankee Station, claimed I was “preoccupied with human unsuccess”. It was not something that had struck me, I must say. I suppose my response would be that in my novels I do test my characters. Things go wrong, sometimes drastically, and the protagonists can only rely on their own human nature and their own resources of character to prevail (or not). This is even true of my James Bond continuation novel, Solo, where I drop Bond down in an African jungle without a gadget or a gun in sight - unaccommodated man - and he has to rely on his own abilities to survive. I think this also touches on the “great theme” of my novels, namely that life is all about luck - the good luck and the bad luck you experience - and that, in the end, explains everything about your short adventure on this small planet circling its insignificant sun.

Of course, Virginia Woolf - as Elfrida is aware - was beset by insecurity. She could not believe that her last novel - Between the Acts - was one of her best. It has a theatrical setting, which makes me wonder how she would have approached the writing of a film. Strange to think that, after a long prelude, her career was one of just twenty-five years. You have been publishing novels now for forty. How does all this seem in a time when the industry is changing so much from year to year? Can one hunker down and keep at it regardless?

The industry has changed - and yet it has its reassuring familiarities from forty years ago. However, the basic business of novelists writing a novel and handing it in to their publisher who then makes a book and tries to sell it to readers is still the bedrock of the writing life. Bookshops have changed, Amazon looms large, the internet heralds new opportunities (or does it?) but writers, their books and their readers is the simple nexus that dominates this multi-billion-pound cottage industry which is no doubt very curious and perplexing to the new breed of managers with their algorithms. So much is still uncertain and fickle and random - but in a good way, thank goodness.

As you know, in Hove we have spent some twenty years in defending our Library against closure. This reminds me that A Good Man in Africa's first printing was 1500 copies, the bulk of which were bought by public libraries, and that helped to sustain you at the time. First-time novelists do not have that leg-up now - and so readers find it harder to explore a variety of books. You yourself, as all writers need to be, are a great reader. How do you see books' place in this seemingly, exhaustingly screen-driven world?

One good thing about this pandemic is that it has seen book sales increase by 11% and counting. E-books have made bigger gains (though their market is smaller). The thing about a book is that it is simply a great invention. It is like the wheelbarrow, the umbrella, the zip, the button, the fork, the wooden spoon, spectacles, watering cans, the safety-pin and so on and so on. Human ingenuity has come up with these inventions, sometimes hundreds and hundreds of years ago, and they work extremely well. Full stop. There is no need to try and better them. Books are light and strong, they last for a very long time; their raw material is infinite and recyclable; you can give them to other people, who pass them on to other people; they are not expensive at all to manufacture in real terms. This is why the e-Book hasn’t replaced the physical book. The real book just too brilliantly ideal. The new technology isn’t nearly as good as the old. So I believe the physical book is absolutely safe.

Yes, that reminds me that when Graham Greene's The Human Factor appeared in 1978 he wrote a letter to that newspaper about Frederic Raphael's review which had questioned Castle's trousers having buttons instead of a zip. And Greene did so again when Philip French made the same point about the film version. Greene's view was that if a button came off, he could sew it on again but he could not replace a zip - though that's a tenable point of view, I still cannot picture him as a dab hand with a needle and thread.

Quite, and that I am very confident that he'd agree the book will survive as long as there are readers - and theoretically our world is getting more and more literate. Screens are great - but, intriguingly, you really don’t need many readers to keep the world of publishing books afloat. In the USA - population three-hundred million, let’s say - a million-selling book is a rarity. Break out the champagne! That’s not even one percent of the population. Publishing is a kind of niche-industry. But you don’t need any more than that, weirdly. It’s a curious paradox that this vast industry is kept afloat, globally, by a few million readers (and buyers). In Britain by a few hundred thousand (population some sixty-five million).

And, I suppose an obvious question: is there a film in prospect of Trio? Could it be made in Brighton? After all, one of the most surreal aspects of British film is that the recent re-make of Brighton Rock had to be shot in Eastbourne.

No offers so far. I suppose it could be made in bits of Brighton - but we would have to CGI the wide shots to replicate 1968. Not complicated - it’s utterly astonishing how you can fake it with computers these days. My Berlin Cold War spy thriller, Spy City, was shot entirely in Prague. But when you see it, it looks exactly like Berlin 1961.

My goodness, we have been talking quite a while. I think we deserve another glass of wine.

Definitely. Actually, why don’t we just order a bottle?

A good idea! Though I think that puts the kibosh on my plan to go to the Picasso and Paper exhibition on the way back to Hove. I shall have to come back, unless of course this pandemic puts the kibosh on that. I like the word kibosh, I must look it up later in Jonathon Green's great three-volume Dictionary of Slang.

THE IMPORTANCE OF LANCING

New Angles - and Brackets - on Wilde's Duelling Wit

Mrs. Marshall. Of the many names which fill the works and life of Oscar Wilde, hers is perhaps one that few can readily bring to mind, even though she was one of the first to chuckle, hoot, guffaw, marvel at his creations.

Here is a clue. “I assure you that the type-writing machine, when played with expression, is not more annoying than the piano when played by a sister or near relation. Indeed, many, among those most devoted to domesticity, prefer it.” That observation, which sounds as if sprung from a play, appears in an 1897 letter sent by Wilde from Reading Gaol to the loyal Robbie Ross about a long letter intended for Lord Alfred Douglas. Two and a half years earlier, Wilde had also been much occupied with typewriting. From Worthing and elsewhere, as 1894 turned from summer to autumn, he had been despatching manuscripts and duly receiving typescripts far sunnier than De Profundis.

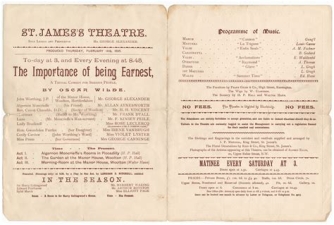

This comedy had gone under various names, cover to keep secret its ultimate title when, by a series of chances, it appeared on the West End stage the following February as The Importance of Being Earnest. It had been staged as early as that, for the actor/producer George Alexander needed something swiftly to replace Henry James's Guy Domville which had received such jeers from the gallery that the author quivered and the run was truncated. Had that play found wider favour, Earnest would have remained upon the platform until the spring - and perhaps never have been seen, overwhelmed by the scandal already being fomented by the Marquess of Queensberry (who had detectives at work on the Worthing seafront where Wilde had sought relief from the task in hand).

Had the passing years seen Earnest emerge from the chaotic sale of Wilde's Chelsea house, it would not have been in the form we know it. Put succinctly, Wilde wrote a four-act farcical comedy, with extra characters and, of course, extra lines; in taking on that work, and supplying Wilde with ever-needed funds, Alexander dismissed him from rehearsals as soon as the first act was done; the way was clear for Alexander to strip it to a farce whose twenty-four hour traffic was accomodated in three acts, a work which met with acclaim (even if Shaw's review was ambiguous).

If secretly narked, Wilde was soon preoccupied by the torrent of events which, despite tacitly offering him the chance of fleeing to France, led to Reading Gaol via that humiliating wait upon a platform - not the Brighton line - at Clapham Junction.

As such, the play has become another example of a work - Sons and Lovers, Tender is the Night, indeed The Picture of Dorian Gray - which arouses contrary views of a definitive edition. Especially as one of the most widely circulating editions of Wilde is the Collins omnibus which prints a four-act version, albeit a hybrid one made by Wilde's son who worked back, in part, from a German edition. It is a reflection upon that country that, in Edwardian times, it was keen to rehabilitate an author whose masterpiece includes many gags about it. A necessary twist in all this is that, in post-Gaol exile, Wilde worked on the play again before its first publication, bravely undertaken by Leonard Smithers who also had a line in louche works. (One might pause to wonder whether his rare name inspired that given to a character in the allusion-hungry series The Simpsons.) In doing so, Wilde added many new, splendid lines to the script which Alexander had created for the first production. A typically resonant addition is Lane's dry remark that there were no cucumbers at the market “even for ready money” - Wilde's parlous exile made tangible. (As it happens, Alexander's script had been typed by a protegée of Mrs. Marshall's agency, one who, as Dickens's grandaughter, had set up a business of her own.)

This makes a cogent case for the first edition being the author's sanctioned text. Some might counter that Wilde did not have his original version to hand and so made the best of desperate circumstances. So saying, anybody who has encountered the four-act version (and the BBC included part of this in a production) must aver that it sags with the arrival of the solicitor and bailiff in the country garden; it loses the brio of what Auden called a verbal opera.

Life is always made joyful by reading, aloud or otherwise, the three-act play whose first-edition additions must make one wonder at all that Wilde could, in time, have achieved had he not become quite exploded in that dismal hotel room. One looks with such sorrow, upon the photograph of his corpse and reflects that a year or two before it was taken - a leap across time - a good friend's father had been beguiled by his conversation while on holiday in France, and, maddeningly, did not write down all that Wilde had said in exchange for a drink. There is no doubt that Wilde could have regained his energies. Every so often, here in Hove, I stroll past the flat in which Lord Alfred Douglas spent the end of his life, and feel irritated at the way in which he distracted Wilde. Be that as it may, as I sit in a house - nearer the sea - in Hove that was built the year that Earnest was first produced, I might be asked why I have spent a fortnight with a play which can be read in an hour.

Before me is a 1200-page two-volume edition whose hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of words might make something by Eugene O'Neill appear a sketch from The Fast Show. And it is all the more fascinating for that. Clive James remarked, somewhere in Cultural Amnesia, that in the time one might give to an author's byways, or even outright mistakes, one can have read another major work by somebody else. True, but, then again, he regards Schubert's songs as a byway from the composer's other works which some of us might, now and then, feel could have benefited from editing.

We all take our own tack upon the allocation of time between now and going underground covered by something which, in all probability, will be more modest than the Epstein creation sadly emasculated by vandals in Pere Lachaise.

Crucially, many of us should be thankful that Professor Donohue has given rather more time to a play upon which Wilde gave those few months. A quarter of a century ago, he produced, after many years' work, a splendid, copiously-illustrated oblong volume, now scarce, which presented the opening-night script of Earnest. In this the coffee table meets the research library (indeed it sits on my coffee table beside the facsimile of Hopkins's The Dublin Notebook, which makes me fearful of using it for coffee). Since then, while working on his two-volume edition of Earnest, it is more than likely that angle- and square-brackets have filled, fuelled Professor Donohue's dreams even if there have been moments when he has woken screaming from a nightmare which turned around losing in a left-luggage office vital material gathered in the Colindale newspaper library (to which, indeed, he had recourse for a definitive contemporary account of how to make a cucumber sandwich, a snack which never fails to bring Wilde to mind: surely a working definition of genius).

These two volumes are the latest part of Oxford's edition of Wilde - something which Smithers, even Wilde himself, cannot have imagined would be the final result of their endeavours. This goes way beyond the edition which Robert Ross produced before the Great War. Among other things, Oxford's edition gathers, in another two volumes, all the quotidian journalism which not only paid Wilde's bills but helped to keep him alert to the passing show which animates best plays and in turn have provided many people with what they take to be a definitive account of everyday life in the Nineties.

To return to these thick, deep-blue volumes. How does a short play full such space?

What we have here is - in essence - the four-act version, seven versions of which are scattered between various libraries (including a text owned by a producer who went down with the Lusitania) – and the three-act one. All of this is attended by cogent introductory essays about the works' evolution and supported, dare I say, rivetted by footnotes which contain innumerable delightful lines that Wilde rightly, reluctantly ditched, as well as those created post-Gaol. On page 172 Professor Donohue makes bold to say: “to appreciate in full the often gem-like qualities of these omissions, the reader should readily give in to the impulse to study passages of the critical apparatus, where these qualities are on full display”.

Well, he would say that, wouldn't he? And he is right. At the very least, the apparatus shows that Wilde was a craftsman, rooted in the Classics, no dilettante dashing off witticisms before breaking open a bottle of champagne at Willis's or somewhere less salubrious.

To present these 1200 pages like that could risk a reviewer appearing as a literary miner, his helmet-light on maximum while crawling through a tunnel in quest of ore to bring to the surface for delectation by others; in fact, all this has felt like a walk across rolling hills on a spring morning, a solace at a time when Wilde's France risks being consigned way beyond the Channel.

Let us forage (in the happier sense of that word), and savour the great dew of Wilde's progress through manuscript and typescript 125 years ago. Symbolic if all this us rhe sub-title's reversal from “A Serious Comedy for Trivial People” to “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People”, a distinction to tax the finest minds.

To the final version of the four-act version Professor Donohue has given the title of Lady Lancing (in which Her Ladyship appears as Lady Brancaster). As Gwendolyn leaves at the end of its Act One, Jack promptly exclaims to Algernon, “There is a ripping girl”, using an adjective whose currency is affirmed by citations from Anthony Hope and Conan Doyle one finds in the OED; Mrs. Marshall had previously typed “what a splendid creature”, which is debatably inferior; come the opening night, it was transformed into “there's a sensible, intellectual girl - the only girl I ever cared for in my life”. To which Wilde, post-Gaol, gave the emphasis, “there's a sensible, intellectual girl! The only girl I ever cared for in my life”.

Earlier, Algernon had provided, in the variously adjusted Worthing draft, this disquisition. “Oh! no chap makes a good husband. If a chap makes a good husband there must have been something rather peculiar about him when he was a bachelor.” Which is all very interesting, but brings so much with it that it holds up the play; even at this four-act farcical-comedy stage, Wilde realised that it had to move on. As it is, all too often in productions of the three-act version, actors pause too long over a line, bringing a laugh which overshadows the phrase which should duly clinch it. One shudders to remember a performance by Nigel Havers: repeatedly mugging, head aslant, almost winking at the audience, he was ignorant of the essential fact that for the play to work those on stage have to play it all for real. That production was only slightly preferable to one in which Hinge and Bracket contrived to take almost every rôle, but, for sanity's sake, we draw a veil over that sweltering evening in the galley.

It is neat when Cecily avers, in an early draft, of the 1874 champagne that “poor uncle Jack has not been allowed to drink anything else for the last two years. Even the cheaper clarets are, he tells us, strictly forbidden to him!” Wilde pruned this, claret deemed a distraction. Come the opening night, all of the '74 champagne had gone (as it were), and Wilde did not reinstate it for the first edition: in art, if not life, he realised that one can have too much champagne.

To keep upon matters culinary - and it is a play as much about that as the funds needed to secure the best of it -, it is a pleasing mark of Professor Donohue's wide knowledge of Wilde that in annotating the likening of Lady Brancaster/Bracknell to a Gorgon, he refers to an 1888 review in which Wilde described James Aitchison's The Chronicle of Mites as “a mock-heroic poem about the inhabitants of a decanting cheese, who speculate about the origin of their species, and hold learned discussions upon the meaning of Evolution, and the Gospel according to Darwin. This cheese- epic is a rather unsavoury production, and the style is, at times, so monstrous and so realistic that the author should be called the Gorgon-Zola of literature”. That alone should inspire more people to seek out Wilde's journalism. In fact, Professor Donohue does not stop there, but alerts one to a full-length, 1986 academic study by Bram Didkstra about the Medusa theme: Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siecle Culture. All of which one might call productive distraction, as is reflection upon the way in which Wilde shifted “exotic fruit” from one character to make best use of the phrase.

Time and again one reluctantly concedes that it was right - early on - to drop such observations as the one which Lady Brancaster made about the Morning Post: “I am sorry, for your own sake, to hear you speak in slighting terms of that admirable journal. It is the only document of our time for which the history of the English people in the xix th century could be written with any regard to decorum or even decency”.

A far cry from the Morning Post was Robert Hichens's novel The Green Carnation which had sport with Wilde and Decadence, and it finds a place in the first drafts of the Army-Lists scene, where Lady Brancaster finds that she is holding a copy by mistake: “This [...] seems to be a book about the culture of exotics. It contains no reference to Generals in it. It seems a morbid and middle-class affair.”

A great in-joke which would now produce scant laughter, the novel becoming a specialised taste, and the joke was swiftly ditched. As for the General, perhaps the play's funniest line, its double paradox requiring swift delivery, is “The General was essentially a man of peace, except in his domestic life.” Earlier, in a previous piece of dialogue, Wilde had her Ladyship state that the General also featured in other lists, such were his unfortunate business speculations. A needless complication, jettisoned. Puzzlingly, though, Wilde did keep in the final version of Lady Lancing typed by Mrs. Marshall a preceding reminiscence by Lady Brancaster: “he was violent in his manner, but there was nothing eccentric about him in any way. In fact, he was rather a martinet about the little details of daily life. Too much so, I used to tell my dear sister.” Rightly, that did not survive the Wilde-less rehearsals before the opening night; Alexander knew what he was about; to have kept all that would have hobbled the subsequent, tighter observation about the General at home, as the exiledWilde must have realised when looking again at the play for a first edition.

As for fugitive invalids, an article could be written - and they have been - about Bunbury. Professor Donohue has scoured the country for him. Odds are, such is the mingling of memory and imagination, that in naming this character, Wilde not only used that of a family friend who had written to him from deepest Gloucestershire with congratulations on winning the Newdigate Prize but he had also seen an 1891 farce Godpapa which concerns a John Bunbury and a ploy to marry his daughter. (Anybody now born with that name will find that he has some explaining to do, just as Wilde's genius has elevated cucumber sandwiches above their humble status.) Professor Donohue writes at length about the rise of nineteenth-century farce (one must hasten to seek out an 1875 comedy Brighton, first staged there and brought to London). One can only drool over the description of the number of theatres then competing for customers, so many of whom were then able to live in the vicinity of the West End; true, many of these productions are now the stuff of sedulous footnotes, but how much more stimulating it would surely be to watch them than yet another of the jukebox musicals which line Shaftesbury Avenue nowadays.

What's more, an evening usually offered a curtain-raiser. Happily, Professor Donohue supplies the American Langdon Mitchell's In the Season, a twenty-minute work which, previously staged, now preceded Earnest each evening during that first run duly halted by the Marquess of Queensberry (it is sometimes forgotten that, the situation brewing, Alexander arranged for a police guard around the theatre on the opening night). In the Season survives brightly, turning around allegations and misunderstandings about a love affair. (We need more short works in this era of television productions which stretch to seven seasons of twenty-four episodes apiece.) Rather than dwell on it, one must certainly note that early on, a character asserts, “I'm in earnest”, which does not seem to have been added for this production.

More than a bonus is an unpublished work by Wilde himself. A Wife's Tragedy has, in manuscript, been available in a library for sixty years but received scant attention. It does not appear in Richard Ellmann's 1987 biography which, unlike his Joyce, is unconvincingly stolid, paling beside Montgomery Hyde's a decade earlier and Matthew Sturgis's recent, highly enjoyable one. Fragmentary, the Venice-set tragedy hints at something which could have remarkable power: a bold spirit should attempt to stage it in some form, and there could be room for a new version of Wilde's scenario Mr. and Mrs. Daventry.

Professor Donohue's two volumes - adding very much to Russell Jackson's admirable 1980 edition – are so rewarding that any intended browse becomes close study, and might even divert one into making cucumber sandwiches according to the instructions provided by the Family Herald when Wilde was at work in Worthing (not that he necessarily read it). One might demur at Professor Donohue's description of Lancing, even in 1894, as “a charming little town on the Sussex coast” and one positively bristles at Howards End gaining an apostrophe on page 858. That is to cavil, for, how can one put it, this feat of humane scholarship produces vibrations. To say that Gwendolyn's phrase perhaps has an erotic timbre which escaped the Lord Chamberlain, and those long after, is borne out by the idea being there from the beginning, when it was briefly the more mundane “it carries vibrations”. One cannot stop writing about this play.