THIS IS NOT DYING

“Relax your mind and float downstream...”. The words are, of course, John Lennon's, but Wonderwall (1968) is invariably recalled – often just in passing - for its soundtrack by George Harrison. Lennon's phrase, however, from “Tomorrow Never Knows”, is an apt summary of a film invariably deemed very much of its psychedelic time. In fact, it proves to be distinctly enduring, even eternal.

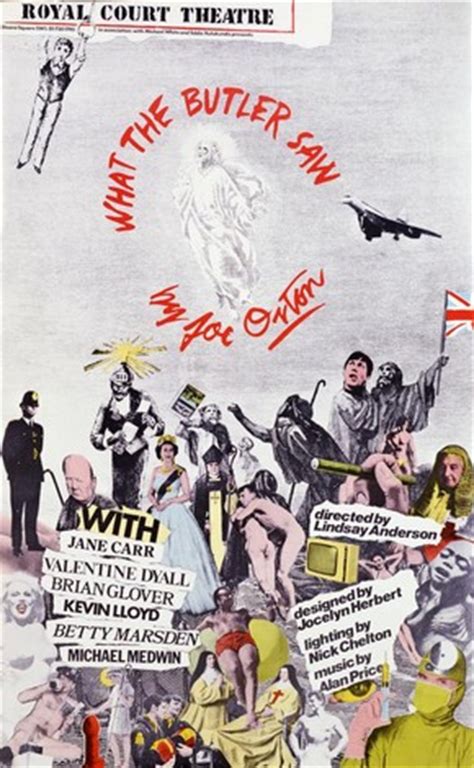

Five decades have brought more to it since its circumscribed initial release, and it has been remastered in a way that brings out so much more than was visible to those who saw it at the time. Here is a film with heritage on every front – including its cinematographer, Harry Waxman who had worked on Brighton Rock and The Day the Earth Caught Fire, and would bring these skills to The Wicker Man. Much of the film's limited funding was given to him – to our eternal benefit. And the rest of that financial pie was divided between such people as costume designer Jocelyn Rickards (whose lover-strewn memoirs are lively stuff), scriptwriter Guillermo Cabrera Infante (the Cuban novelist who wrote a history of cigars Holy Smoke), all of it brought together by director Joe Massot who had a palpable skill at networking long before the term was created.

Consider the cast. Here we encounter that actor much favoured by Beckett, Jack MacGowran; a wonderful turn by an ever-thwarted cleaning lady (Irene Handl); Jane Birkin (who sometimes sheds the costumes given her but, alas, does not mention the film in her recently-published diaries); and Richard Wattis (familiar as many a bespectacled, officious clerk in English films).

To what were all these, and more, put in a film whose sets were designed by a collective known as The Fool (mostly remembered for designing the exterior of The Beatles' boutique on Baker Street, to the outrage of the local Council)? As it happens, the opening of the film is now distinctly topical. MacGowran is in a laboratory and looking through a microscope. As George's rock 'n' raga music plays, microbes swarm in all their psychedelic glory, and are later echoed in several animated sections a year before Monty Python reached television screens. Such close-up work has had a troubling effect upon MacGowran, who returns to a flat which bears all the traces, and more, of an obsessive. Even he can find it's all too much (to deploy the title of another George song), and one evening hurls at an exposed-brick wall one of his framed collections of butterflies. These break loose – and, amidst their fluttering animation (very Yellow Submarine), dislodge a brick, which opens up a view of neighbouring Jane Birkin.

This is a vision so fascinating that MacGowran, who has quite a taste in hats, removes more bricks to gain a perspective of what he takes to be free-and-easy living. The censorious might say that this is voyeurism. Something more subtle is going on: his neighbour, and her visitors, are equally unsure of themselves, and, such is the turn to events, he proves to be an unexpected hero, a force on behalf of life. This is not dying, as the rest of John's opening line to his terrific song puts it.

To convey in prose so very visual a film is not easy, one becomes immersed, even a very part of events in which a fridge can loom larger than it ever does in life (there is a great variant on asking a neighbour to “borrow” milk: Jane Birkin's lover seeks... bananas).

This is a film which, having taken one so long to catch up with it, leaves one eager to see it again. If not an unknown masterpiece, it is far more than the curiosity of legend. George Harrison's hunch was correct. This was something to which to give his time amidst the rigours of The White Album. How on earth was he paid? After all, this was a millionaire who had came up with the opening chord for “A Hard Day's Night”, a defining moment in English film. The producers of Wonderwall could not afford the music rights, and so he was able to release the album of it on Apple (as chance has it, a fruit which appears, probably not as product placement, several times in the film), but the music gains so much in its visual context.

What's more, room is found for an, er, spot-on poem by none other than John Lennon, about the nature of: lanolin.

It is all haunting, wonderfool (to coin an adjective), so unexpected. Come to think more and more about it, this is perhaps a near-masterpiece. The disc, especially on blu-ray, is not only a tribute to its restoration but brings with it a real, 32-page booklet which contains more than any reviewer can incorporate. Time can work miracles.

Of course, this was not the first film in which a Beatle branched out into a film score. Paul had been asked to supply one for the excellent The Family Way. As the deadline loomed, he hummed a piece – which anticipates the glorious “Here, There and Everywhere” (his own favourite) – and George Martin worked up the orchestral incarnation. With Wonderwall, the other George was hands on, recording pieces to the exact second in Bombay, and drawing upon the non-Indian help of Eric Clapton and Tony Ashton (who should be better known for his great Seventies hit “Resurrection Shuffle”).

Watch Wonderwall, in the 1968 option, rather than the truncated "director's cut", and it takes one in so many directions which perhaps began with Paul's enthusiasm for Magical Mystery Tour, a film which also continues to gain its rightful stature.